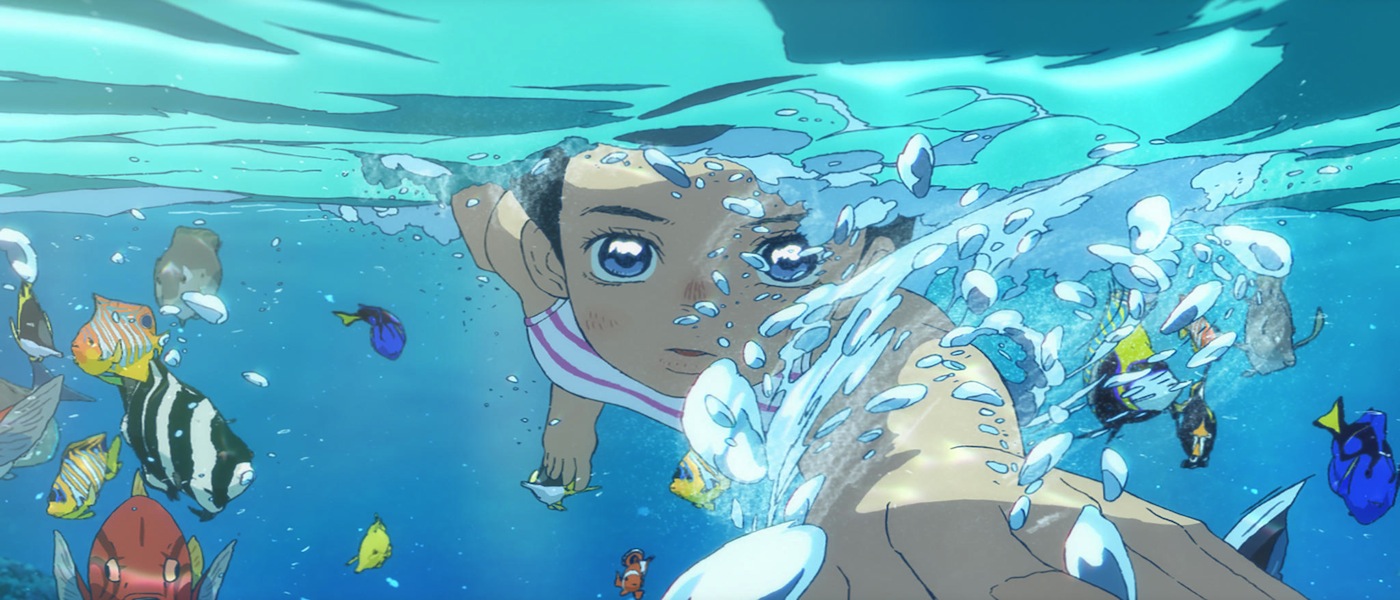

English Dub Review: Children of the Sea

Overview (Spoilers Below):

Children of the Sea presents the story of Ruka, a girl who finds herself going through the motions in life, but particularly passionate about the ocean and all things related to the environment. Ruka continues to appreciate and be fascinated by the sea, but her life becomes considerably more interesting after she encounters Umi and Sora, two mysterious boys who aren’t just also passionate about the ocean, but seem to share an unusual connection to it.

Ruka’s gentle coming of age experience and her new friendship with Umi and Sora coincides with a strange supernatural event that nobody seems to have an answer for. Ruka is devastated to learn that fish and creatures of the sea are disappearing without explanation. Ruka desperately tries to solve this problem with her new friends, as well as attempt to understand how they may be linked to this strange event, too. Ruka soon finds herself in an unbelievable situation that will forever change the way that she looks at a body of water.

Our Take:

Children of the Sea is a beautiful film with a strong message that unfortunately happened to come out in a year that’s simply full of incredible anime feature films, like Promare, Ride Your Wave, and Weathering With You. Children of the Sea may turn out to be the weakest of the lot of these exceptional films, but that’s far from a condemnation of this movie. Children of the Sea is a very accomplished, powerful film that more than anything should put Ayumu Watanabe on people’s radars. This is easily the best film in his growing library of work and he’s absolutely someone to keep an eye on. His next film could even surpass the works of these other acclaimed directors.

Children of the Sea effectively juggles both huge global issues and more intimate personal drama. The film is able to properly capture a simple elegance where even muted moments where Ruka looks at her neighborhood and environment become joys in themselves. The movie digs into that authentic, slice of life, small town charm aesthetic that the works of other directors like Makoto Shinkai or Masaaki Yuasa do so well. Children of the Sea excels where the mundane becomes extravagant and simple human experiences resonate in huge ways, as if the audience are the characters that experience them. These kinds of movies specialize in celebrating the beauty of one thing in all of its glory, which in this case, is the sea and the life that it contains. Children of the Sea makes these pieces of nature seem like they’re pure magic.

The animation in Children of the Sea has a gorgeous baseline where it always looks stunning. There’s a professional quality to Watanabe’s work, especially with the lighting and shadow in scenes or with the character designs and people’s emotion-filled faces. There’s still enough of a roughness to this that makes it seem a little imperfect, like real life. Facial expressions and scenery come to life in amazing ways and there are some stupidly eye-popping sunsets in this movie, but the true highlight here is how the water and sea life are animated.

These environments pop in a whole other way and there’s such love in the animation behind it all. Masterfully, the material registers at a higher level and the film makes sea creatures and water look as stunning to the audience as they are for Ruka. They stand out in a way where their significance is always clear. On that note, the fish and various sea creatures all look so incredible that I could have easily just watched another fifteen minutes of Ruka passively admiring exhibits at the aquarium. The killer whale sequences will seriously drop jaws and could be released as a short film of its own that would still impress. There are some incredible swimming sequences where characters’ heads bob up and above the surface of the water and one marvelous scene where the luminescence of the water helps light up the characters in an enchanting glow. Any time somebody approaches a body of water in this movie it becomes a reason to get excited for what’s about to play out in the animation. Ayumu Watanabe and his team at Studio 4 °C capture this stuff so beautifully and the film arguably wouldn’t work if this level of wonder wasn’t present.

Ruka’s final journey into the depths of the sea (as well as the creatures within) also plays with color and lighting in such inventive, satisfying ways. Everything culminates together in such a powerful last act that feels worthy of this epic journey. It should also bring many fond memories of Jabu Jabu to mind for any Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time fans. The movie also cleverly switches between styles to evoke more of a Katsushika Hokusai aesthetic for certain elements and characters that’s really effective in how the sparse use of clashing techniques stands out. There are some particularly fantastical moments where Ruka’s imagination gets away from her and weather masquerades as sea life in beautiful ways that do oddly feel reminiscent of Weathering With You and Ride Your Wave, but the moments are brief and are more rooted to Ruka’s malaise than driving forces to the story.

The characters in the film are also pre-teens, which can sometimes be a problematic age, but Children of the Sea captures their naïve innocence as well as their bumbling cruelty. There are many directors who devote their entire careers to creating these realistic, raw relationships and stories and even though Watanabe’s back catalogue isn’t as extensive as others, he really nails the character dynamics here. The relationship between Ruka and Umi is hardly original, but it still connects and will likely evoke tears from the audience.

It’s fair to say that Children of the Sea does begin to feel very familiar once this fantastical boy begins to help open a girl’s life up to the world, but it’s also still beholden to the manga that it’s adapted from. Children of the Sea does present a story that’s been seen before in many different iterations already—even with an environmentally conscious message at its core—but it’s still a very enjoyable, successful animated film. On that note, Children of the Sea does have a socially minded agenda, but it presents it in a way that’s touching rather than awkward or blatant. In many ways it brings 2019’s Penguin Highway to mind and this would make for a fantastic double feature with that film.

Children of the Sea explains that Umi and Sora are from a “world beyond imagination,” but keeps their origins otherwise brief. This plays to the film’s strengths with the cryptic nature of these will o’ wisps and how they’re connected to nature. Around the film’s midway point there’s a seismic event that takes place that imbues Ruka with Sora’s fantastical abilities. As she tries to protect the environment and the things that she’s passionate about, she deals with changes of both a supernatural and human nature. The moments of psychic bonding between Ruka, Umi, and the sea life that follow are some of the most poignant sequences in the film and they typically all play out silently sans dialogue. It also oddly made me think of the Ecco the Dolphin games in a way where if SEGA ever wants to re-launch the series as an anime, look no further than Ayumu Watanabe and his team at Studio 4 °C.

The vocal performances are all a delight, but it’s the score and music work in Children of the Sea where the audio truly shines. Joe Hisaishi, a frequent collaborator over at Studio Ghibli, handles the film’s score and he conjures a very similar magic with his work on this film that he’s done over at Ghibli. The music gradually changes between enthusiastic anthems, gentle lullabies, and it even becomes very folkloric when it evokes the pan-flute and accentuates the fable-like nature of this story. The film’s theme, “Spirits of the Sea,” by Kenshi Yonezu, is also very appropriate.

Children of the Sea amounts to a pleasant film where it’s very enjoyable to spend an extended period of time with these characters, but the story still feels very small at times. The film’s ending gets very philosophical and cosmic in a “we all are one” kind of way and that this is all a part of a cycle that feeds into itself. The big finale comes down to a special meteor and how it will help regulate the planet, but in doing so it seems like it will rid the Earth of its sea creatures in a fantastical big bang-esque experience that will spur on a whole new universe of life, but at the expense of Earth.

This whole “I am the universe” segment is extremely trippy and shows what this film is really capable of doing when it lets loose and doesn’t hold back. It’s a dazzling feat that feels reminiscent of epic conclusions from films like The Tree of Life and 2001. It’s a huge surprise, but the somewhat restrained nature of the rest of the film makes this animated assault hit even harder. It unleashes all of its best tricks at once and overloads the screen with one of the best visual delights that you’ll see in cinema all year. This sequence alone makes this a must watch movie and it’d be a real contender for best animated film of the year if this year wasn’t somehow subject to many incredible animated movies.

Children of the Sea’s ending also tries to spin a larger message about how the world is made up of a balance of good and evil, but it tries to equate this to land and water creatures, as well as humans and will o’ wisps, in a particularly clunky manner. Children of the Sea says that everyone is the same in the end and that we all need to put aside these differences or we will just continue to suffer. However, this is a level of metaphor that’s really not necessary and the film still stands on its own without trying to reinforce this heavy-handed theme at the end.

Children of the Sea is a rewarding achievement of animation that will take many viewers by surprise. It tells an effective story that may be reductive in some ways, but it’s full of lovable, realistic characters and some of the best visuals of the year. Children of the Sea doesn’t reinvent the genre, but with the amount of fun and passion that’s present in this film, it’s proof that that’s also okay.

"There are also other characters that come and go (also owned by the Warner Bros. Discovery conglomerate media company)."

Huh. Is that just referring to other characters from the show itself, or is this implying that the new season is going to have cameos from other WBD IPs